London’s universities are big players in the capital’s economy as well as a visible presence on its streets. They account for 85,000 jobs – more than in the advertising, and architecture and engineering sectors, and almost as many as in accountancy and law – and their economic impact has been valued at £27 billion every year.

Our leading universities are truly global institutions: University College London (UCL) and Imperial regularly feature in global “top ten” rankings, and foreign students make up a large proportion of London’s student population – a success in terms of exports and soft power.

But London’s universities also have a good story to tell about their local impact, and in particular their offer to students from less advantaged backgrounds. Two recent exercises, which I reviewed for University of London, have sought to evaluate how the UK’s universities compare in terms of supporting social mobility by attracting and boosting the careers of students from poorer families or places.

Two years ago, the Sutton Trust and the Institute for Fiscal Studies (IFS) analysed how well universities did in attracting students who had been on free school meals at age 16 and how many of these were in high-earning jobs at age 30. The ten highest-performing universities by these measures were all in London, with Queen Mary University of London, University of Westminster and City University of London taking the top three slots.

A slightly different approach was taken by Professor David Phoenix from London South Bank University. His English Social Mobility Index, which has now been published for three consecutive years, looks at how well students from deprived places perform in terms of access to courses, continuation and completion rates, and then earnings and “graduate employment” one year after graduation.

The 2023 index shows Bradford and Aston universities in the top spots but five of the top ten are London institutions: City, King’s College London, London School of Economics and Political Science (LSE), Queen Mary and UCL.

Neither approach is perfect. No, graduate earnings are not the only measure of the value of higher education. Yes, London is at an advantage because graduates who stay in the city will earn higher salaries (even if most of those evaporate in rent and travel costs). And, yes, focusing on the deprivation of places rather than people does not reflect the differing geographies of poverty inside and outside London.

However, the indices do seem to show London universities – both established institutions with global brands and newer former polytechnics – doing relatively well. This is partly because Londoners from poorer backgrounds are more likely to go to university: 44 per cent of London pupils on free school meals go on to university compared to 27 per cent across England, and eight per cent go to more demanding “high tariff” institutions, compared to four per cent across England.

This is partly a tribute to the performance of London schools, which have shifted from being the worst performing in the country to the best over the past 20 years, particularly for pupils from poorer backgrounds.

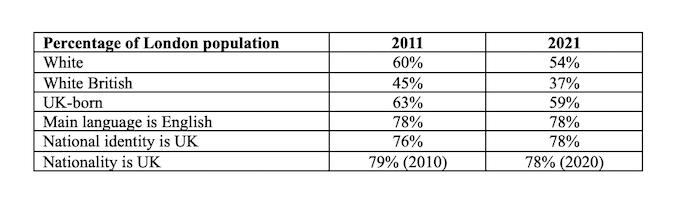

The reasons for this have been intensively debated, with some analysis pointing to the investment and focus that came with the London Challenge, and others arguing that it is the ethnic make-up of London’s young population that is driving success – put bluntly, white British pupils drag down the results in other parts of the country.

Some of London’s most successful universities certainly have an intake that reflects the high levels of aspiration in many minority communities: Queen Mary, City, LSE, Imperial and Westminster all have disproportionately large intakes of students from UK Asian backgrounds, though fewer universities (East London, West London, London Met and Middlesex) do so well in recruiting UK Black students. These broad categories also gloss over any differences within different groups, for example between Indian and Bangladeshi, and Black Caribbean and Black African students.

But London’s universities also do well in offering courses that attract students from poorer backgrounds, particularly those looking for a stable and well-remunerated career. Pharmacology, computing, law, economics and business offer the strongest social mobility dividend, according to the IFS/Sutton Trust research.

Nineteen of the 20 top courses in these subjects are in London, with Queen Mary and City universities in the vanguard. And universities work to tailor their courses to student circumstances: in interviews for University of London, teaching staff at Queen Mary emphasised the flexible approach they took to timings and teaching approaches to support students with caring responsibilities, of whom they have a relatively high number.

High participation rates in London show how far university attendance has been normalised here for young people from all backgrounds (in contrast to apprenticeships, where the capital has the lowest take-up of any English region). This may partly result from the widespread presence and visibility of universities, but is also driven by the demands of London’s job market: in 2016, 53 per cent of jobs in London were held by someone with a degree, compared to 30 per cent in the rest of the UK; for senior managerial jobs, the proportions are 64 per cent in London and 38 per cent elsewhere.

But it’s not just the managers. People working in administrative or elementary manufacturing roles are also more highly qualified in the capital. These graduates working in such “non-graduate” jobs may account for London having the lowest proportion of graduates saying that their work was meaningful, fitted with their plans and used the skills they developed in university. Scores were particularly low for those graduates who had lived in London before going to university.

So, London universities play an important part in London’s success as a “social mobility hotspot”, showing how access to higher education can be widened for all classes. There may be opportunities to widen the hotspot: universities from across the UK have opened outposts in London; perhaps London universities could work with local partners to open satellites elsewhere. However, low job satisfaction levels for London graduates also suggests that more needs to be done outside universities, to make work fulfilling for all and to help young Londoners to access a diverse range of post-18 education and training.

Originally publcished by OnLondon