I was probably sixteen, working in the kitchen of the village pub, when I first heard Black Sabbath.

“You like heavy metal,” said my boss, a hairy biker avant la lettre.

“I so do not,” I replied, thinking of Def Leppard, Iron Maiden and Bon Jovi.

“Nah, you do. You liked that Led Zeppelin tape I played. Now try this.”

What the…?

The churning, sludgy guitar sound, the desperate voice of a man struggling against the mire of the music and his mind. The sense of grubby doom, then suddenly tempo changes, keyboard washes and jazzy drums, and guitar solos that sounded like they had been recorded in a cave. I loved it all.

I grew up near Banbury. Not that close to Birmingham, but not that far either. The Mercian dankness could creep down the A41. Black Sabbath followed me when I started working at a greenhouse factory a few years later – pressing aluminium, not forging steel, but still. We had Radio 1 on all day (Kylie and Jason, Cliff Richard, Mike and the Mechanics), but Sabbath and Zeppelin ruled in the rattly old Mini Metro that I drove home. Those heavy guitar sounds are as much a part of those days as the styrofoam boxes of chips and beans from the food van at lunch.

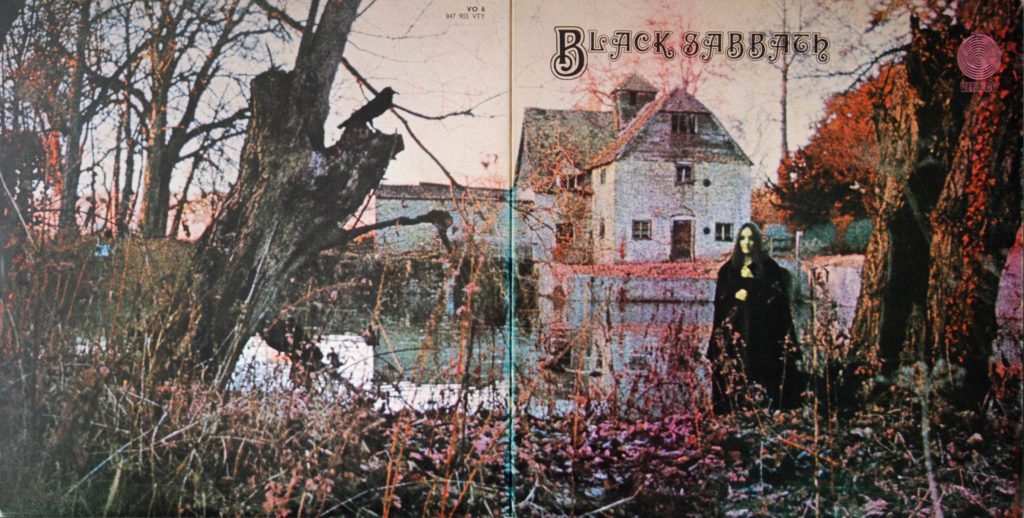

As Quietus founder John Duran has argued, Black Sabbath’s was defiantly modernist music. It didn’t hark back to blues, to skiffle, to folk, to chanson, or to big band. It lived in its own world, a world of factories and factory closures, a world of managed decline and derelict mills.

And I think that’s the point. Black Sabbath’s early albums are constantly surprising, because they don’t know what they are meant to be. The perfect powerpop of Paranoid is sandwiched between lumbering leviathans War Pigs and Iron Man. Proggy epics such as Wheels of Confusion sit next to the blissed-out hippy bongos of Planet Caravan. Of course Black Sabbath didn’t know how to play classic heavy metal; they were too busy inventing it.

RIP Ozzy Osbourne