The Office for National Statistics (ONS) is something of a national treasure – independent, rigorous and accessible, and always ready to speak up when statistics are bent out of shape by politicians.

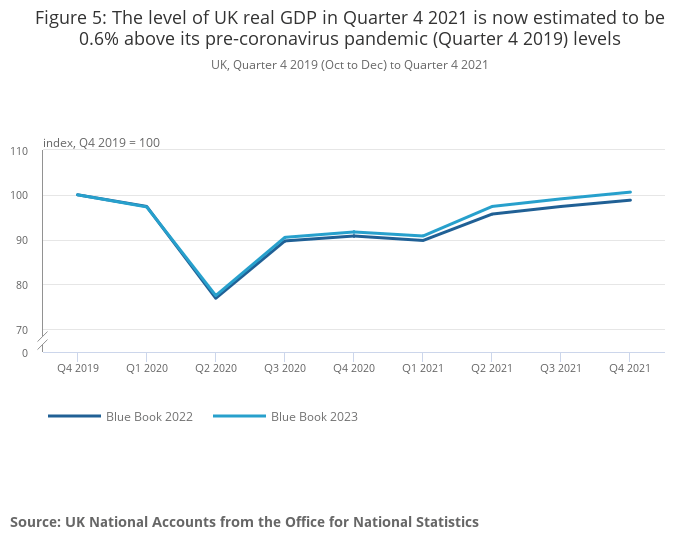

It is also ready to hold up its hand when it gets things wrong. It did so last week, when it revealed that it seemed to have been undercounting GDP growth since the pandemic. The changes meant that UK economic output had bounced back above its pre-pandemic level by the end of 2021, rather than remaining below it. More significantly, this put the UK in the middle of the pack of G7 countries (above Germany, level with France, and below the US, Japan and Italy), rather than languishing below them – though ONS does warn that these countries too may revise their calculations.

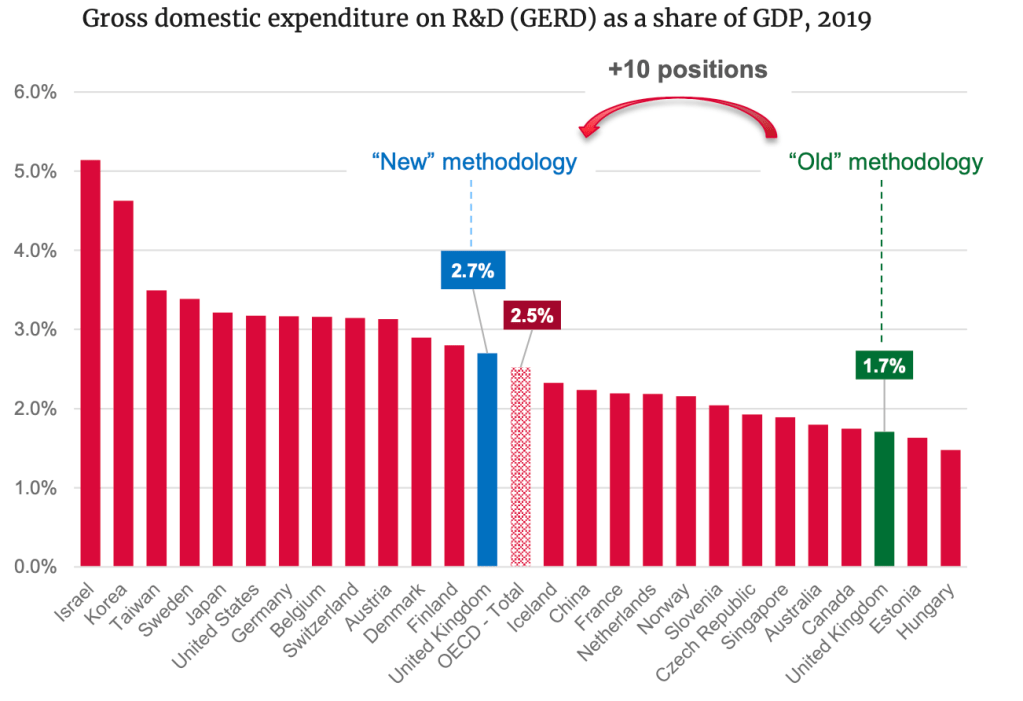

I came across a similar correction recently, when comparing UK expenditure on research and development (R&D) to other countries’. When the UK Government’s Innovation Strategy was published in 2021, it made much of the fact that we were only spending around 1.7 per cent of GDP on R&D, well below the OECD average. A target was set to raise expenditure to 2.4 per cent of GDP by 2027.

Last autumn, the ONS reviewed how small business expenditure on R&D was being assessed, and revised its figures. UK expenditure on R&D in 2019 rose from 1.7 per cent to 2.7 per cent, bringing it above the OECD average, and putting the UK ahead of China as well as many of our European neighbours. By 2021, we had moved further up the table, spending 2.9 per cent of GDP on R&D, against an OECD average of 2.7 per cent.

Source: UK Innovation Report 2023

These numbers too may change again, and the changes are an illustration of the difficulties of measuring something as complex as an economy, particularly in the wholly exceptional global circumstances of the past few years. I’m really not qualified to say whether such dramatic revisions call for a review of how statistics are compiled. However, as Tim Leunig has stated in arguing for such a review, these changes matter because low GDP and low R&D investment matter. They are the basis for changes in policy (including, I suspect, the repeated expansion and extension of the UK’s R&D tax credits regime), so if the data are wrong, then policy may be wrong too.

But I am struck by how ready I was – and I suspect I am not alone in this – to accept as a simple fact something that actually seems to have been very wide of the mark. Of course the UK is underperforming most other advanced economies, I thought, Of course it is. It’s ‘sickmanism’, our reclamation of the dubious accolade that seeemed ours by right in the 1970s, a return to the “orderly management of decline” that permeates John Le Carré’s novels of that time.

It’s not surprising that many of us are ready to believe the worst. After seeing public services and social infrastructure stripped to the bone over a ten year period, the ever-deeper impoverishment of society’s most vulnerable, a needless and needlessly harsh split from our closest allies and trading partners, and a succession of political leaders who seem to treat politics like a fairground card trick, I can forgive my own cynicism.

The annoying thing, of course, is that our frankly middling performance (playing catch-up with Italy?) will now be hailed as a triumphant vindication of Brexit and the sound economic governance that recent administrations have been known for. Chancellor Jeremy Hunt has already said that it disproves the “declinist narrative about Britain and its long-term prospects”.

But beyond the political ping-pong, perhaps there’s a lesson too: it is not to flip from doomster to booster, but to treat assertions of the UK’s global decline as cautiously as those of its triumph. Maybe Britain can make it after all.