The 2021 census, conducted in March last year, will forever be a strange record of a strange time – hard to interpret but fascinating for what it doesn’t tell us as much as for what it does. The first results, covering broad population figures, came out in June, and further detail will emerge in the coming months and years, with more expected in the autumn.

The census was already the subject of intense political debate because, as On London has reported, census figures underpin funding formulas for everything from schools to fire services. Undercounting London’s population may rob our public services of resources even as the cost of living crisis deepens.

Past censuses have been criticised for missing many Londoners, for example undocumented migrants who may be unwilling or unable to complete official forms. In 2021 there was the added impact of the pandemic: city-flighters, students stuck at home, hopeful immigrants and emigrants stymied by travel restrictions.

So we should be cautious when looking at London’s census results. But what do they tell us about how London is changing – from cradle to care home – compared to the rest of the country and compared to previous decades?

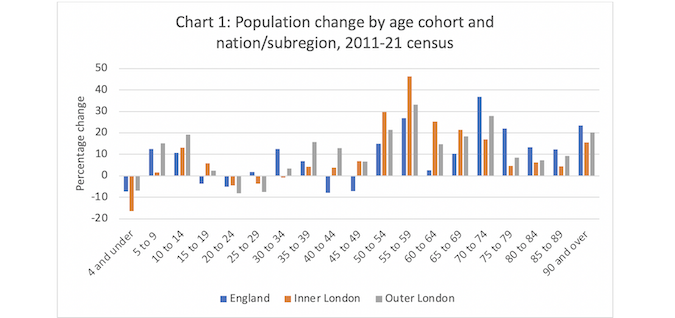

The two charts below summarise the numbers. The first compares the 2011-21 population changes for inner London, outer London and for England as a whole.

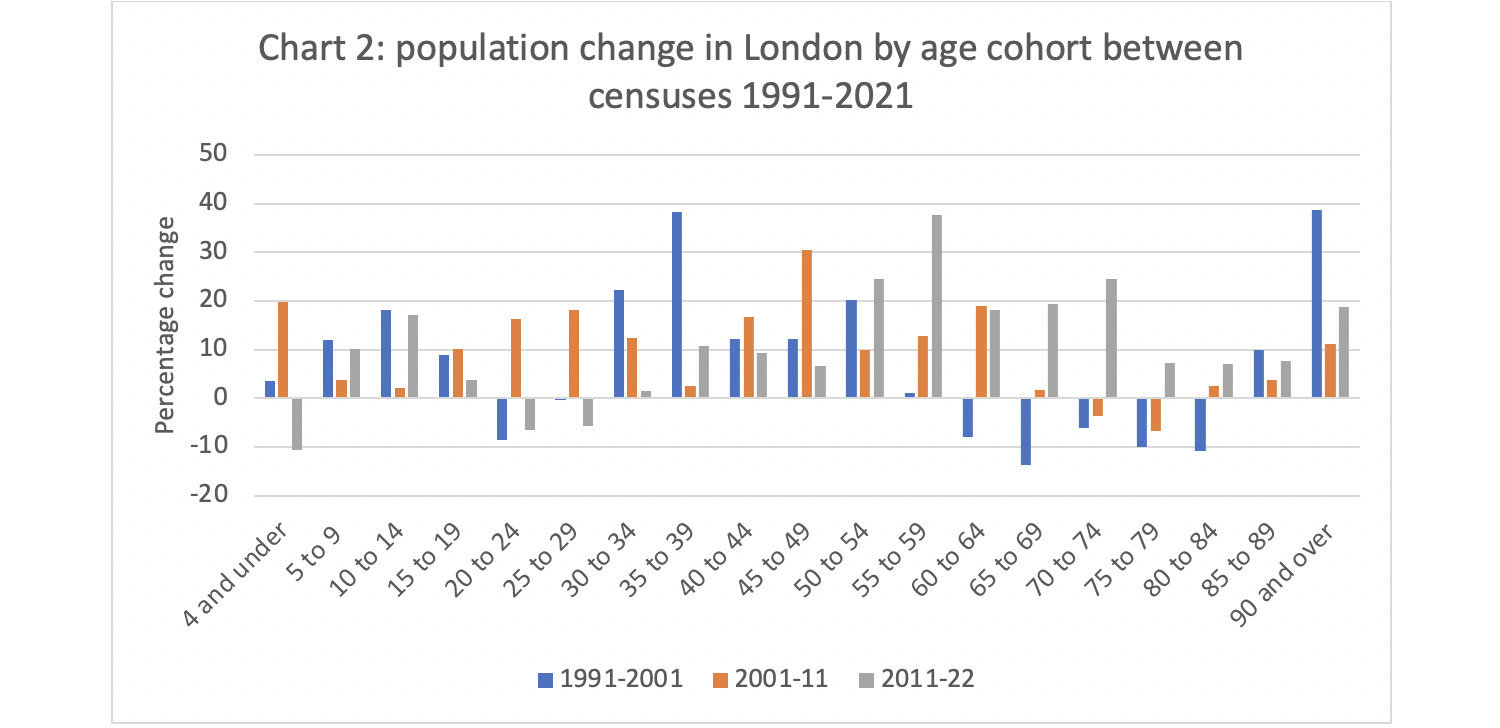

The second puts these changes in context by comparing the last decade in London with the findings for the capital of the previous two censuses.

Here are five conclusions that can be drawn.

One: Baby boom and bust spells turbulence for education authorities

London had a baby boom between 2001 and 2011, adding more than 100,000 under-fives (a 24% rise in the age cohort). This was reversed in 2011-21, with the numbers of under-fives dropping particularly fast – by 16% in inner London.

Some of this change may be the result of young families moving out temporarily during the pandemic but, as Greater London Authority demographers have explored, the birth rate more or less peaked around the time Boris Johnson started boasting of a London 2012 conception bonanza and has fallen back since then.

This makes planning school places fiendishly complicated: while demand for primary places fell in most of inner London, the outer H-boroughs (Harrow, Hillingdon and Hounslow) saw some of England’s highest growth rates for primary age children. And as the 2000s baby boom fed through, the secondary school cohort has grown much faster: Barking & Dagenham’s 10-to-14-year-old numbers grew by 43%, the fastest in England, with Hounslow, Richmond and Tower Hamlets close behind.

Two: London’s loss of young people was rural counties’ gain – at least temporarily

Between 2001 and 2011, 15 to 30-year-olds accounted for a net growth of around 300,000 people (around a third of London’s total net growth), reflecting the city’s magnetic pull for young people seeking to study, work or simply enjoy their lives. This contrasts with the overall stagnation in that population group in the previous census period spanning 1991 and 2001 and what looks like an almost comical reversal of the early century trend between 2011 and 2021. Rather than flocking to London, twenty-somethings seem to have headed down some deep country roads. For example, Test Valley, East Devon, Maldon and Harborough have seen the biggest rises in their numbers of 25 to 29-year-olds.

Some of this probably does reflect long-term relocation to new hipster heartlands of the West Country and the Kent and Sussex coasts, driven by soaring London rents and the ever-wider availability of flat whites. But I suspect that much more of this apparent exodus has already reversed, as young people who moved back to parental homes during the pandemic or began their university studies online have returned to larger towns and cities. The GLA’s helpful guide to the census uses payroll data to show just how many early-twenties workers left the capital during the pandemic and came back in autumn 2021.

Three: London’s boomers are booming

London’s middle-aged population (yes, including “Gen X”-types as well as “Boomers”) has soared, seeing some of the highest growth rates in England. The number of 55 to 59-year-olds in inner London grew by more than 45%, including by around 60% in Southwark, Lewisham and Lambeth. This contrasts sharply with England as a whole, where this age group grew by a more modest 27%. The London growth is also much faster than in previous decades: the 55 to 59-year-old population increased by 13% between 2001 and 2011, and by a negligible 1% the previous decade.

Some of this probably has its roots in London’s rapid growth of 35 to 39-year-olds in the 1990s, though of course there will have been plenty of churn between the census years. But it is interesting to consider why this generation may have chosen to stay in the city – and in inner London in particular – a rather than moving to the suburbs or a Home Counties village.

This was a generation that was able to benefit from relatively low house prices in the early 1990s following the property crash at the start of the decade. As mortgages are paid off, properties that were bought for tens of thousands of pounds are now valued at ten times as much. At the same time, since the pandemic, there has been a nationwide fall in the number of over 50s in the labour market.

It’s too early to join the dots convincingly between these trends – to say confidently why the numbers of middle-aged people have risen so fast in inner London boroughs. But we can speculate. Is this a “boomer belt” of reasonably well-off homeowners? People who may have stopped working and don’t feel the same financial pressures as younger Londoners in precarious housing, some of whom don’t see any great urgency in building more houses in established neighbourhoods? Interestingly, Brighton and Hove, which has similarly high housing demand and constrained supply, has seen a very similar demographic shift over the past decade.

Such stability makes for liveable neighbourhoods and lively local shops, cafes and restaurants. But at what price? If high prices and low supply squeeze younger and poorer people out of the inner city neighbourhoods, or even block them from moving there in the first place, stability may be at the cost of vitality and – in the longer term – economic productivity.

Four: London is ageing, even though not as fast as we thought

If London’s boomers stay in the city we will also see a big bulge in the older population when we come to review the 2031 census. Over the past ten years, London’s sixtysomething population has grown a lot faster than the English average. Among the over 70s, growth has been slower, though boroughs such as Waltham Forest and Redbridge have been closer to the national average.

As the GLA predicted, the census figures showed that previous estimates had over-done the size of London’s elderly population. However, growth is coming, and as today’s 60-year olds enter their seventies around the time of the next census, there will be a corresponding growth in demand for health and care services, making their currently dysfunctional funding and management an ever more urgent issue for London. It will also bring into sharp focus the issues of specialist housing for older people that were explored by my former Centre for London colleagues last year.

Five: Something was happening in 2021, but we don’t yet know what it is

The pandemic was probably more disruptive for London than any event since the Second World War (when no census took place). While its impacts were not as cataclysmic for city living as some predicted, we still don’t know what the long-term effects will be on working patterns or on how and where people choose to live. Nor do we know how new immigration arrangements, political change and the looming recession will affect the capital.

There may be a case for a mid-term census in 2026, as suggested by economic geographer Danny Dorling. But London will undoubtedly need to draw on data from the latest census and beyond to understand the city, who it is working for, and how it is changing.

First published by OnLondon.