Sir Sadiq Khan was right to highlight the potentially “colossal” impact of artificial intelligence (AI) on London and its economy in his Mansion House speech last week, but “controlling” this still-emerging technology may be a tall order.

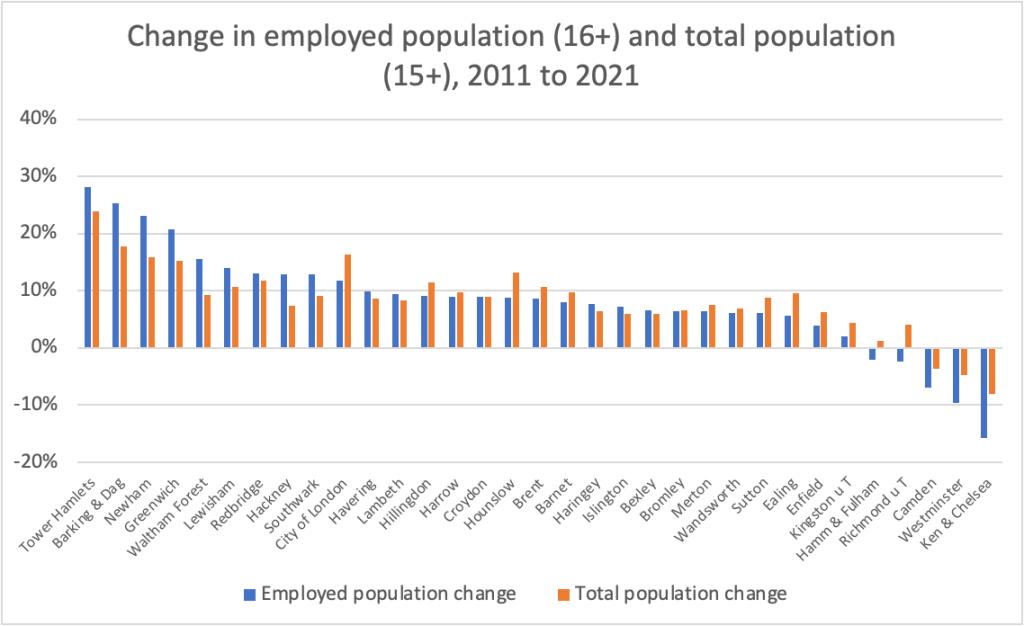

As the Mayor argued, the dominance of knowledge economy sectors in the city puts London “at the sharpest edge of change”. Three such sectors – information and communication, finance and insurance, and professional, scientific and technical services – account for 31 per cent of jobs in the capital, almost twice as many as across the UK.

These are the roles that are most exposed to AI. Human-centric, a report written by me and published by University of London in October, argued that generative AI’s ability to “precis, to research, to generate ‘ideas’, to structure arguments and data, and to produce text and images make it a close fit for tasks that are core to knowledge economy roles”. AI boosters and think tanks alike predict that these sectors may be as dramatically shaken up as agriculture and manufacturing were during previous spates of technological change.

However, the impact is hard to discern at the moment. There may have been a fall in graduate recruitment, but the evidence is contested and the impact of AI hard to disentangle from other factors. And corporate adoption of generative AI has been slow. This is partly about accuracy and accountability, but also reflects the ways in which generative AI use is spreading: individual workers are using chatbots on mobile phones and desktops rather than technology introduced through complex, top-down corporate roll-outs.

But it is still early days, only three years since ChatGPT 3.5 was launched, even if it seems longer. And so, while things may feel calm for the moment, there could be a storm coming, with London’s economy directly in its path. The impact on employment could, as the Mayor said, be dramatic.

It bears repeating that generative AI does not simply “take jobs”. The technology can be used to support particular tasks (“augmentation”) or to fully automate those tasks (“substitution”). If this saves time and money, it boosts productivity: more output for the same input.

Productivity gains may be realised by redeploying workers to build more products or serve more customers, or to develop new products and services. Such gains can also be shared with workers in the forms of reduced hours or higher pay. But they can also be cashed in, to return money to shareholders or taxpayers, through “efficiency savings” – that is to say, job losses.

There are ways to slow this down, but they are not necessarily desirable. The US think tank Brookings has proposed a “robot tax” on automation to tip the balance in favour of keeping humans in work (and to create revenues that could support workers who lose out).

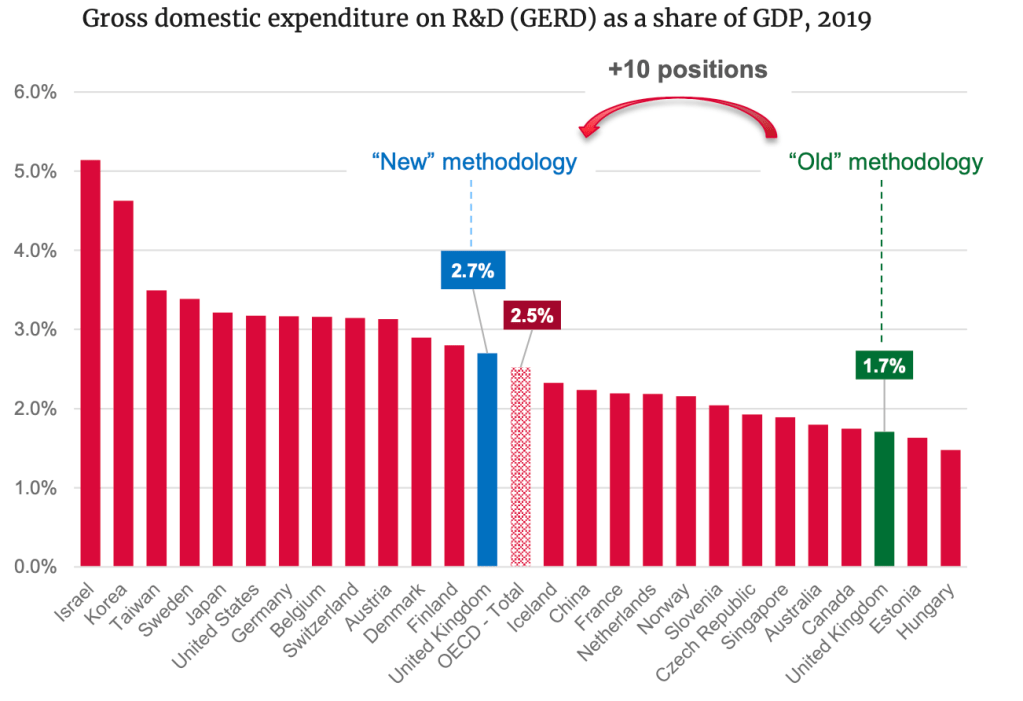

Regulations could also be used to slow AI adoption. But keeping humans working on tasks that could be done more efficiently by AI makes productivity gains much harder to achieve and poses a particular threat to cities like London, which export and compete globally. We can throttle back AI adoption here, but will Singapore, New York and Dubai follow suit?

London is actually well-placed to seize the opportunities that come with AI: the city is a world leader for AI investment and innovation, with a highly educated, cosmopolitan population and a bedrock of world-class universities. The city is also a centre for innovation, for creating new products and services, and for the highly personalised and specialised professional services that may be most resistant to automation.

Even if AI adoption in London leads to job losses, history suggests that technological change leads to the creation of as many jobs as it destroys. We have done this before: automation of London stock market transactions – part of the Big Bang of 1986 – took work away from hordes of back-office clerical staff, who previously had to reconcile every trade on paper. These jobs went, but new jobs – in IT, as analysts, in compliance – led to a net growth in financial services employment.

That said, there is a time lag, and the net gain in jobs can obscure the traumatic impact on those people who lose out. The Mayor’s commitment to offer AI training to all Londoners will be valuable. Human-centric argues that universities should play a part too, helping workers to develop the skills they will need to thrive in and shape the new world– part of the much vaunted shift towards lifelong learning.

Universities can also ensure that the next generation of graduates has the resilience and skills to thrive. This is partly a matter of technical skills, but also about knowing how to use a deceptively “easy” resource critically and ethically, putting this in the context of a wider understanding of citizens and society, and nurturing the human skills – of judgement, understanding, collaboration – that employers still see as paramount.

The Mayor’s Mansion House speech touched on a bigger issue too: the “unprecedented concentration of wealth and power” that could result from AI adoption. The risk is that productivity gains from the use of AI flow mainly to big tech companies and their shareholders, rather than to workers and the public at large. This is beyond the reach of city or even national governments, but will become increasingly urgent if AI adoption does create a boom. What good is growth if its fruits flow to a few people in Silicon Valley?

There are ideas out there – from a levy based on how many hours of computational time individuals and firms use, to an endowment that takes a proportion of the value of AI companies launching on the stock markets and uses it endow a “universal basic income” that enables everyone to share in the benefits of AI.

However, adopting any of them will require a level of international cooperation that seems almost impossibly remote in today’s fractured geopolitical climate. Perhaps this is an issue where cities can take the lead, hoping that their national governments will catch up over time.