London’s population reached a historic high of 8,945,300 in the middle of last year, according to new estimates released by the Office for National Statistics. After slower growth at the end of the 2010s and a slight decline between 2019 and 2021, the number of people living in the city rose by 0.9 per cent – around 75,000 – between 2022 and 2023, the fastest growth rate since 2015-16.

Does this suggest that London has escaped the twin shadows of the Covid-19 pandemic and Brexit and is returning to its turbo-charged growth of the late 2000s and early 2010s? Well, maybe and up to a point.

Certainly, the capital has defied some of the more apocalyptic predictions that emerged during lockdown – of the age of cities stuttering out in an “urban doom loop”. But it is still growing more slowly than other UK regions and metropolitan areas, most of which grew by one per cent or more in 2022-23. London’s growth rate is in fact more like what other regions were experiencing ten years ago, when the capital’s population was surging by 100,000 or more every year – a growth rate of up to 1.4 per cent.

London is also growing a bit more slowly than experts forecast. The mid-2023 estimate is very slightly lower than that of the most cautious Greater London Authority (GLA) population projection, which was based on the 2021 Census and projecting forward the slower growth trends from 2017-21.

Borough patterns suggest a mixture of recovery and longer-term trends. In some places, the return to growth looks like a post-pandemic rebound. This is most notable in Camden, which saw one of the steepest declines in population at the beginning of the pandemic but has now more than recovered, with 2.9 per cent population growth between 2020 and 2023.

But there appear to be broader trends operating too. Hillingdon, Tower Hamlets and Newham have each shown persistent growth, adding at least four per cent to their populations between 2020 and 2023. On the other side of the equation, Lambeth, Lewisham, Haringey and Waltham Forest all have populations that remain two to three per cent below their pre-pandemic levels.

Even if London’s growth has slowed, its population dynamics remain distinct from those of other parts of England and Wales. The capital continues to see much higher international inward migration (around 154,000 in the year to mid-2023) and domestic outward migration (130,000 in the same year) than other regions.

The capital’s population is also buoyed by natural change – the surplus of births over deaths – which accounts for growth of 50,000 in the year to mid-2023. Meanwhile, across England and Wales this has dwindled to nothing or gone into reverse, with as many people dying as being born for the first time in 42 years.

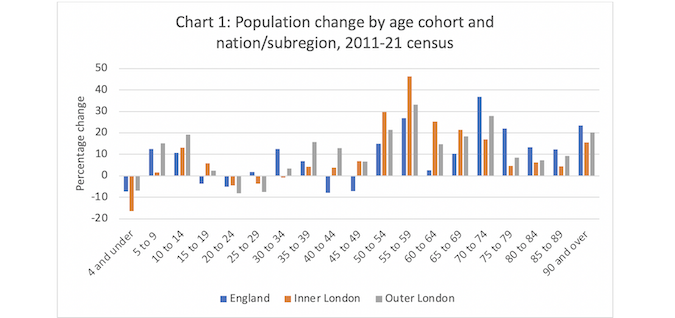

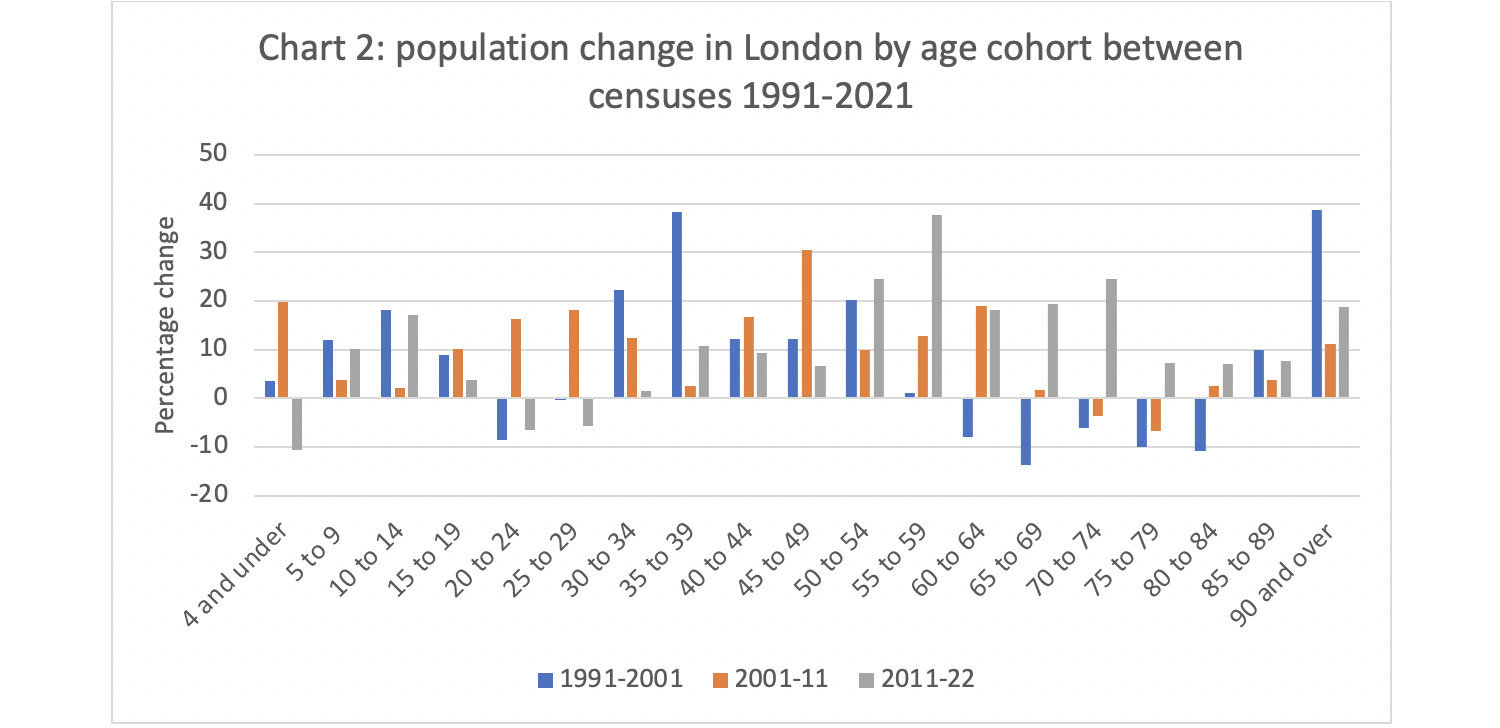

London is still younger than average (both a factor in and a result of its natural growth rate): its median age is 35.9, compared to 40 or older in every other region in England and Wales. The age groups that have seen the fastest growth since the pandemic abated (2021) are people in their twenties and in their sixties. However, longer-term (since 2011) the twenty-something population has declined, and the fastest growth has been among Londoners in their fifties and sixties – maybe those who lucked out by buying property in the 1980s and 1990s.

International comparisons suggest that London is not alone in its population growth patterns. Slow recovery is the norm following Covid, and other large northern hemisphere cities were already seeing a slowdown before 2020. US Census Bureau estimates suggest that in 2023 New York City’s population was still six per cent below its April 2020 total, though population loss is slowing. Paris has also seen a long-term decline, largely as a result of falling birth rates, which accelerated during the pandemic.

Cities have not gone away, but their slow recovery perhaps reflects the unexpected “stickiness” of changes in working habits and a sedate return to international migration patterns. If that is so, London’s slow growth may just be a delayed bounce-back. Comparisons with the GLA projections suggest this might be the case: those projections modelled growth slowing in 2022-23, whereas in fact it speeded up.

It may also be that growth is constrained as the cost of living in the capital remains sky-high and London struggles to meet the London Plan’s housebuilding targets, let alone the more ambitious goals suggested by the last government and think tanks such as Centre for London.

This should be a cause for guarded optimism. If policy and delivery are constraining growth we can turn that round, adopting the “Get Britain Building” mantra of the new government. London can build its way back to sustainable growth as a liveable and exciting destination for UK citizens and international visitors – provided of course that other measures, such as arbitrary immigration restrictions, do not stifle the UK’s world city.

First published by @OnLondon.