Interviewed on Radio 4 for the launch of his re-election campaign on Monday, Sadiq Khan said this year offered “a moment of maximum opportunity for Londoners, for there’s the prospect not just of a Labour Mayor, but of a Labour government working together [with a Labour Mayor].”

Even if the tone was more bullish than the Labour leadership might like, Mayor Khan has a point. Since he was first elected in 2016, he has lived with a chaotic kaleidoscope of Conservative governments. When these have shown any interest in the capital, it has generally been to frame it as an overheated reservoir of “wokery”, or to attack Khan’s record on policing and planning – most recently through directing a review of industrial land and opportunity area policy, announced the day before the pre-election period formally began.

Khan’s predecessors were luckier. Ken Livingstone’s first term started with him politically homeless, expelled from Labour for running as an Independent against their official candidate, Frank Dobson. The early days, when I was working in the Mayor’s office, were notably scratchy: Livingstone’s first meeting with Deputy Prime Minister John Prescott was cryogenically chilly, his battle against the London Underground public private partnership poisoned relations with HM Treasury, and I remember the air turning blue as he offered London minister Keith Hill his frank thoughts on provisional spending settlements.

But Livingstone benefitted from coming to power when the public spending taps were being turned on, and when the Labour government led by Tony Blair wanted to show that its new devolutionary settlement was a success. By 2004, following back-channel discussions with Number 10 and a more publicly visible collaboration with culture secretary Tessa Jowell over the London 2012 Olympics bid, he was back in the party.

Buoyed by London’s unexpected success in winning the Games, Livingstone’s second term saw substantial public spending in London, government and parliamentary approval for Crossrail – today’s Elizabeth line – and new legislation that extended the Mayor’s powers on housing, planning, culture and waste.

Boris Johnson benefitted from this legacy following his election in 2008. And from 2010 Livingstone’s Conservative successor had the following winds of a Conservative-led coalition in his sails.

He too secured more powers, through the Localism Act and and the Police Reform and Social Responsibility Act, both passed in 2011. And although London boroughs’ budgets were cut heavily – as were those of other urban councils – the government was surprisingly generous in investing in the Olympic Park legacy, including Johnson’s pet project, Olympicopolis (now East Bank), perhaps aware that just as a successful Olympics can show off a city, a tumbleweed-strewn legacy can show it up.

The only initiative that failed to make any headway was the London Finance Commission, a deliberately non-partisan campaign for fiscal devolution, which was beached on the sands of Treasury insouciance in 2013, and again in 2017 when Khan had a second go.

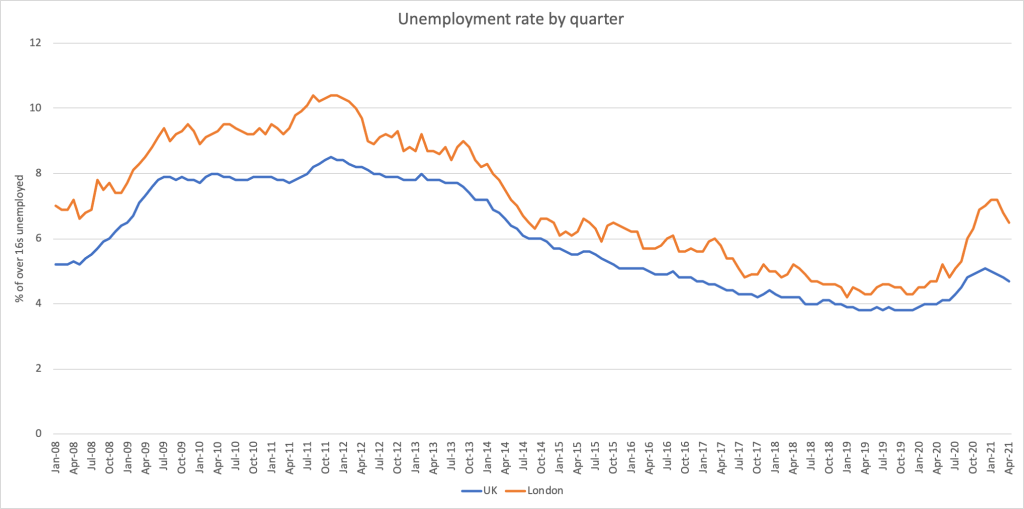

Khan came to power in spring 2016, as the five years of public spending cuts started to take their toll and the European Union referendum campaign slouched to its self-harming conclusion. The years since have been dominated by a grim procession of crises – Brexit contortions, the Covid pandemic and spiralling inflation – which have seen the Mayor and the government on the opposite sides of arguments, with spending decisions marked by public spats and denunciations rather than the private haggling and public consensus that operates between political allies.

While the “metropolitan elites” of London became useful villains, “levelling up”, the regional policy boondoggle Johnson wielded in the 2019 general election campaign, has little to show by way of results apart from cancelled and delayed projects, funding and tax decisions that do down the capital, and occasional outbreaks of opportunistic culture war posturing.

So Mayor Khan can be forgiven for believing, in words that still carry a faint resonance from the 1990s, that “things can only get better” if he wins a historic third term. Labour have said little about their plans for devolution beyond a promise of legislation and speeches focused on bringing some consistency to the patchwork quilt of devo deals spread across England. Furthermore, the UK’s dismal fiscal outlook suggests that “turning on the taps” of public spending is still a distant prospect. But Labour’s economic growth mission cannot pass over the opportunities London offers.

There could be a golden moment ahead. By the end of the year, a Labour Mayor and a Labour Prime Minister could be simultaneously in post, short of cash but rich in political capital. Starmer and Khan have their differences – on relations with the EU and Green Belt development, for example – but must be able to agree a shopping list of measures that are cheap and capable of having a real impact on growth and prosperity, even if some are controversial.

Such measures might include selected urban extensions in the Green Belt, more fluid European work permit arrangements for young people, performers and professionals, rail devolution in London, and maybe one more push for a system of fiscal devolution that enables London (and other English cities) to manage local taxes and local development.

Sadiq Khan has been quick – on occasion too quick – to point the finger at central government for everything wrong in London. A double win in the capital this year would give Labour a chance to show just how much better the relationship between City Hall and Whitehall could work.

Originally published by OnLondon.