This is a family story, an unexceptional but striking vignette of the British Empire.

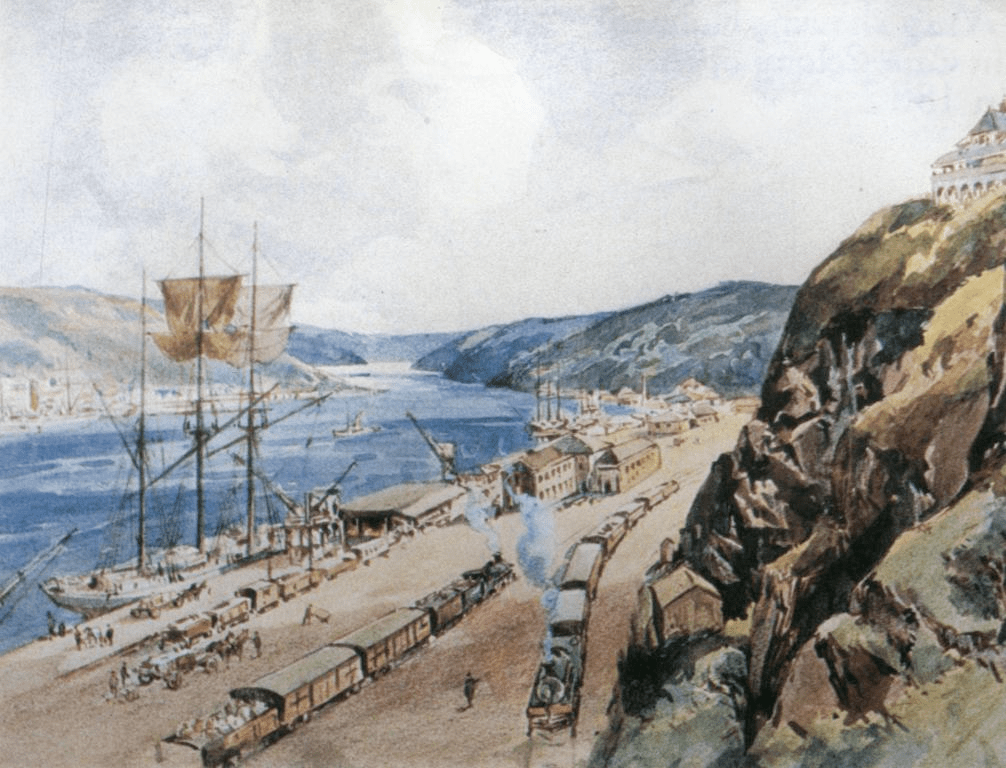

On 20 November 1857, The Lady Kennaway made anchor at East London, South Africa, having sailed from Plymouth, England, two months earlier. The ship was a rough passenger ship (in poor shape by then, judging by the fact that it had been refused insurance that year), about 121 ft long. Following its launch in Calcutta in 1817, it had been chartered by the East India Company, and subsequently transported convicts and settlers to Australia.

The Lady Kennaway was wrecked a few days after landing, but not before its passengers had been disembarked. They included 153 women and girls, collected from orphanages and workhouses across Ireland (filled to bursting point by the Great Irish Famine of 1845-49), and taken to South Africa to marry demobilised soldiers.

These soldiers were not British, but mainly German mercenaries, recruited to fight for Britain in Crimea, and relocated to South Africa after the war (which they had barely fought in) had concluded. The British governor’s idea was that they could form the basis of a colonial settlement (and be rescued from the twin perils of intermarriage and homosexuality) by bringing out marriageable women. One of those women was my great-great-grandmother, Margaret Gallagher.

What must it have been like for her, plucked from the trauma of Ireland aged 20, where she had probably seen friends and family die from hunger, transported across the ocean in an ageing hulk and dropped into the heat of East London, the bright sunshine of a Cape spring, with the uncertain prospect of being married off to a soldier she had never met?

Margaret seems to have been lucky. She took up with Patrick Lowry, one of soldiers escorting them to King William’s Town, the provincial capital (now called Qonce). They married and had numerous children (family sources seem unsure of precise numbers), the second-youngest of whom, Annie, was born in Gibraltar, presumably a new posting for Patrick. Annie subsequently married and settled in Essex, where our lives overlapped for a year in the early 1970s.

As I said above, the story is far from exceptional – there must be 152 others like it from that one journey – but it is one little instance of how the great machine of the British Empire scooped people up and moved them halfway across the world, like so many pieces on a chess board.

It recruited foreign mercenaries for a Black Sea war, found it couldn’t use them, and shipped them to settle the lands from which the British had displaced Dutch settlers (who had in turn displaced the indigenous Khoikhoi through warfare and disease). It created orphans through negligent famine in one place, and sent them halfway across the world as soldiers’ concubines. It could be a surprisingly mobile and inter-connected world, but a cruel one too.