‘Record levels of dissatisfaction with the NHS‘ seems to have become an annual headline fixture, dusted off each year around this time, when the King’s Fund and Nuffield Trust publish the health findings from British Social Attitudes.

This year was no exception, with just 21 per cent of people expressing themselves ‘satisfied’. But what exactly are people dissatisfied about, and what do they want done about it? Given the importance of debates about the NHS, it is worth diving into the figures to understand a bit more.

1. Wait in vain

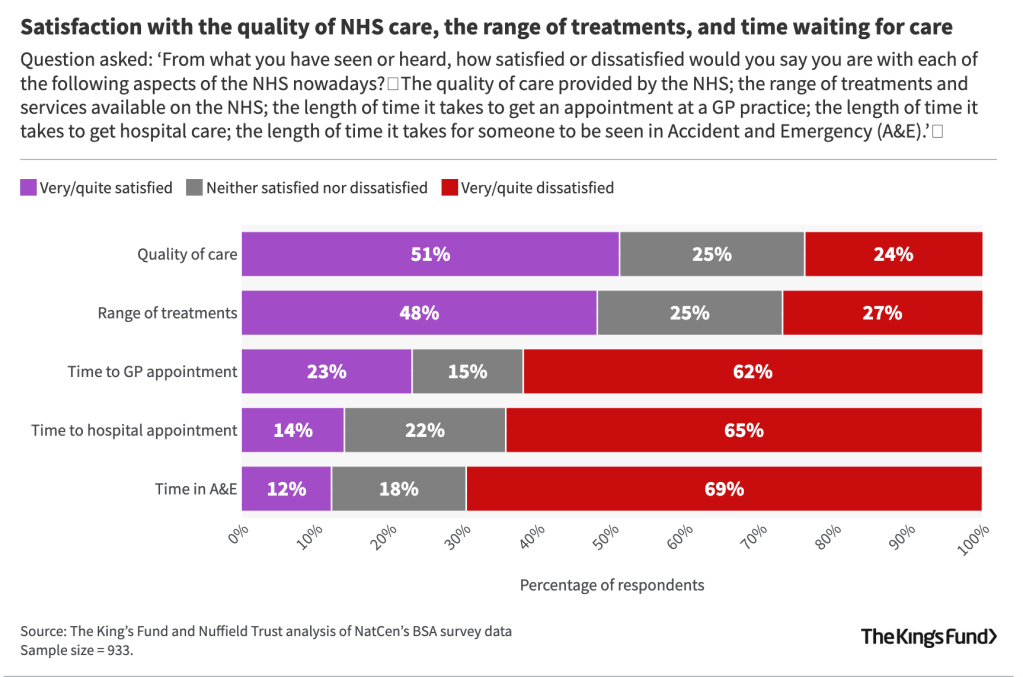

Dissatisfaction is rife across services – from dentistry, to GPs, to A&E, to hospital care, to social services. But it is the time spent waiting – in A&E or for GP or hospital appointments – that rankles most. Only 25 per cent are unhappy with the quality of care or the range of treatments available; around 50 per cent are satisfied.

The problem with NHS care is the quantity provided not the quality – as is also reflected in 75 per cent saying the NHS is understaffed. Produtivity and enhanced outcomes are important, but unless these lead to more responsive services, they may do little to shift public perceptions.

2. No tax, only spend

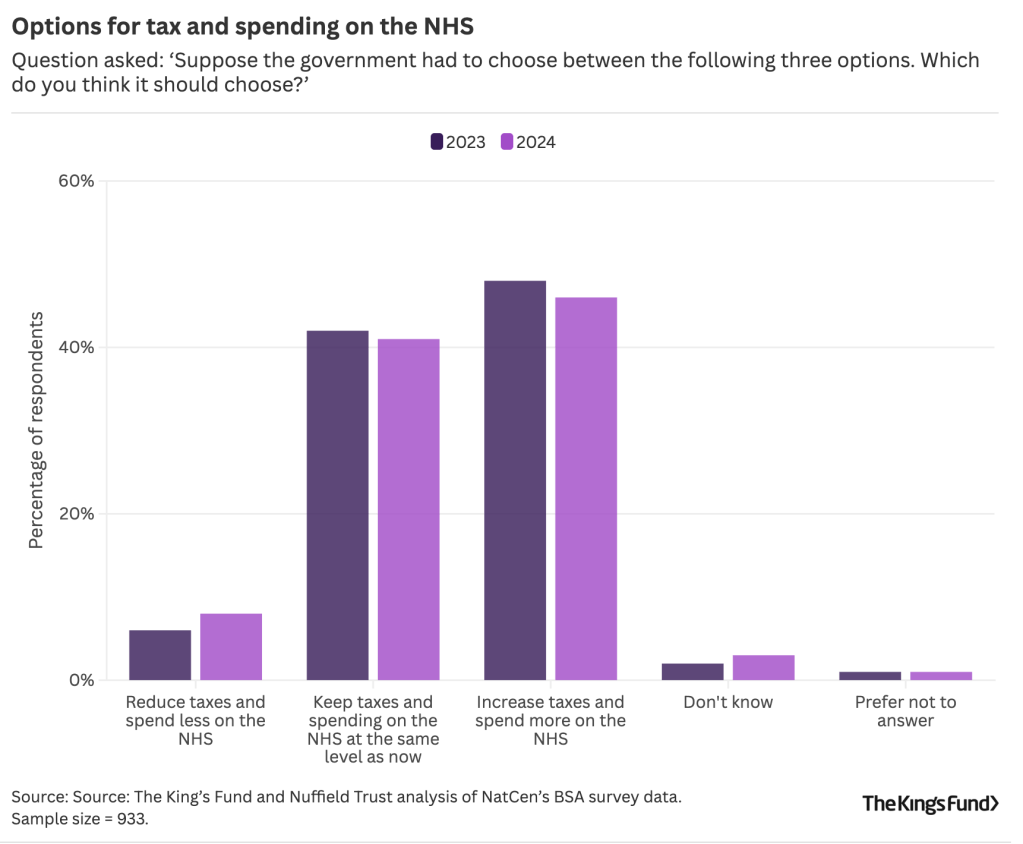

Nearly 70 per cent of people think that the government should spend more on the NHS, but only 46 per cent think taxes should go up to do this, a very slight fall from 2023. These views are not necessarily inconsistent with each other, or with the government’s policy, which has been to spend more on the NHS without raising personal taxes.

But I wish that British Social Attitudes would ask a follow up question, both on this specific issue and on their more general finding that the public wants to pay more tax for better public services, and has done for almost a decade. ‘Which taxes do people wish to see rise?’, they should ask or even ‘Do you think you should pay more tax?’ I suspect that there is far more enthusiasm for tax rises in the abstract than there is for the specific, let alone the personal. I may be wrong, but it would be useful to know.

3. Shaky foundations?

British Social Attitudes also asks about whether people sign up to three ‘founding principles’ of the NHS – universality, freedom at point of use, and funding through taxes. Bea Taylor from Nuffield Trust is quoted as saying, “support for the core principles of the NHS – free at the point of use, available to all and funded by taxation – endures despite the collapse in satisfaction.”

Well, up to a point. Support for the NHS being free of charge at the point of use has been sustained. But there are signs of change elsewhere. The proportion of people saying the NHS should be definitely available to everyone has fallen from 67 to 56 per cent since 2021, and the saying taxpayer funding definitely applies has fallen from 55 to 42 per cent. These are pretty substantial shifts.

The biggest gains have been both those opposing the propositions, and those feeling that the propositions ‘probably’ apply. It seems support for these core propositions, while still broadly intact, is less fervent than it once was – a change that could be attributed to anti-immigrant feeling (for the ‘universal’ principle), to a rise in Reform-driven debate about ‘insurance-based models’ (which the party is rather coy about), or simply to people thinking that something has to give.

As the Government prepares to launch its Ten Year Plan for the NHS, it will be interesting to see what that might be.